An American coot skittering on the vernal pool in the Chicken Flats, an ephemeral wetland that once expanded into the San Francisquito Flats when beavers were common. Photo by Andrew Evans.

What Happened to California’s Beavers?

January 17, 2023

By Andrew Evans, Conservation Grazing Associate

Every major river in California, except the Smith, is dammed… but no longer by beavers. Towering walls of concrete contain reservoirs that are filling rapidly to the brim with the recent atmospheric river deluge, threatening to breach and destroy all that lies in their path. So far this month, we’ve received more than 11 inches of rain in Monterey County. How much of this water will trickle down through the soil and recharge our aquifers, and how much will rush out to the ocean having only splashed the surface? Water managers across the state are beginning to address these questions in new ways to shape how California can mitigate the impacts of drought and adapt to a changing climate.

In September 2022, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) launched a beaver restoration project that aims to tackle drought by reinstating beavers to their former, wide-spread glory. Known as “ecosystem engineers,” beavers are highly skilled in slowing and storing water. The corollary impacts of their natural dam-building activities include restoring wetlands, boosting biodiversity, and increasing ecosystem resilience.

Beaver History in California

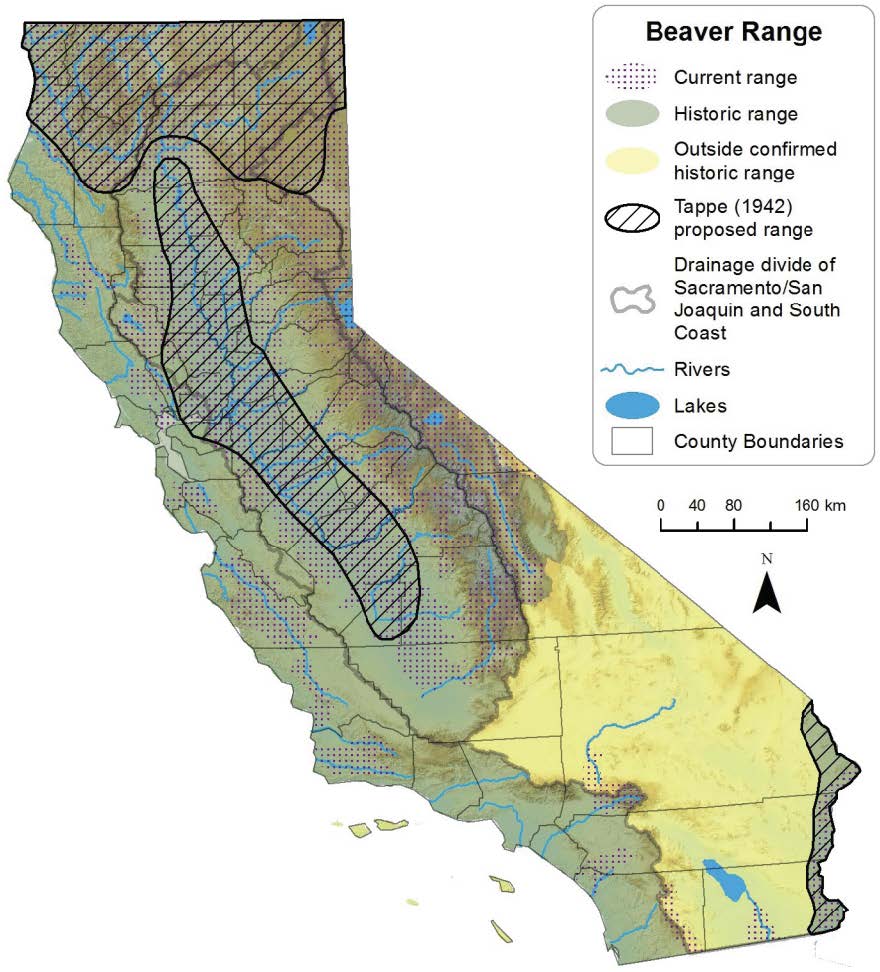

Until recently, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW; previously the California Department of Fish and Game) held that the North American beaver (Castor canadensis) was not relevant to the California landscape, relying on a 1942 examination of beavers’ range in the state. Developed from trappers’ journals (as early as 1827) and extant beaver refuges, this report erroneously confined the beaver’s range to the Central Valley, limited drainages in Northern California, the Colorado River in Southern California, and, within those locations, only in areas below 1,000ft in elevation. For reference, the San Francisquito Flats on The Preserve lies at 1,400ft.

The 1942 baseline excluded the Central Coast and southern California from their proposed natural beaver distribution, convinced by observations which still hold true today: the land was simply too arid, with streams dry for a large portion of the year, stream beds too rocky and steep, and little beaver food (willows, aspens, and cottonwoods) available. However, doubt is rising as to whether this condition always held true, and whether our experience of California landscapes today is one missing a crucial element.

Within the past decade, a swell of pro-beaver activists, scientists, and journalists have sparked a re-imagination of California’s natural landscape. A revived investigation of historical records, modern place names, and traditional ecological knowledge supported a 2013 updated review, which found that California was once overflowing with beavers. Ben Goldfarb’s book Eager: the Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter critiques the original 1942 report’s journal sources, which were recorded after decades of beaver exploitation by trappers, colonists, and merchants. Beaver advocates not only suggest that beavers inhabited most of California, but that they dammed nearly every stream in North America with an average of 17 (and up to 83) dams per mile.

The CDFW now acknowledges that beavers are a keystone species with a historic population estimated at 100-200 million across North America. The agency’s new beaver restoration program is a promising opportunity to bring beavers back to the Central Coast, as well as all the benefits they bring with them.

Beaver range map, courtesy of the California Department of Fish and Game.

Ecosystem Engineers

Beavers are ecosystem engineers, which means they actively convert and create habitat, which both suits their needs and the needs of all other species dependent on those habitats. By building marvelously messy dams along drainages, packed with branches and cemented with mud, beavers trap water in place. While beaver-less streams drain completely and remain dry until winter rains return, beaver ponds trickle water from their base slowly enough that their ponds can stay wet year-round. When winter rains reach a beaver pond, water spills outward, creating wide, shallow, marshy wetlands. By catching and slowing stream water, beaver dams let larger portions of surface flows seep into the ground rather than drain downstream—that means beavers can be the key to restoring our currently depleted groundwater. Water managers are now experimenting with similar man-made structures they call “recharge basins” or “infiltration basins,” while beavers have been doing this service for more than 3 million years, cost-free.

By pooling water, beavers also speed an essential wetland process: sedimentation. As water slows down behind a dam, any sediment slurried into the water begins to sink and settle. Over time, this sediment builds up, and with flooding at the stream’s margins, wetland plants begin to grow onto this newly laid sediment. The vegetation traps even more sediment, and, eventually, what once was a beaver pond becomes a wide meadow full of spongy sediment and organic material. Dam by dam, built, abandoned, or even swept away, beavers morph narrow-cut rivers into wide, meandering terraces of meadows and active wetlands. They actively change the topography, creating a dynamic interface between wet and dry land.

Beaver meadows are a fascinating climate solution, as their spongy, organic, and rich soil stores water that might otherwise cause severe flooding. What is particularly enlightening is the reverse process. When beavers are removed from a system, streams flow faster and begin to erode sediment deposits, cutting themselves lower and narrower into the bank. These cuts, as they continue to erode, eventually drain away the previously terraced soggy, and biodiverse wetland, leaving the surrounding area drier and increasingly more vulnerable to flood damage. This is the California we live in today.

Example of a functioning beaver pond in the Sierra Nevada mountains, Max Odland/American Rivers.

Building Dams, Beaver Style

While restoring beavers to their rightful place in California ecosystems is a process still in its early stages and is led state and federal agencies, there are ways to promote the benefits behind beaver engineering. Just as beavers jam stream flows with woody debris, ecologists in California have started building beaver dam analogues (BDAs), which mimic the design, form, and function of natural beaver dams using available woody debris. By implementing BDAs in channelized streams, scientists are working to restore wetlands. These initial attempts at holding water can contribute to increased wetland area, sedimentation, flood resilience, and biodiversity. Down the line, BDAs might even create habitat enticing enough for beavers to return to the area on their own.