2020 is a celebratory year for the Conservancy – it is our 25th anniversary, a notable milestone. The vision of a unique conservation community is becoming a reality, with Preserve families working in partnership with our small, dedicated land trust to care for 20,000 acres of scenic, storied and ecologically diverse lands. Today, the Conservancy’s nine staff members work closely with landowners and Preserve staff to carry this vision forward through actively stewarding our natural lands, engaging the community in these efforts, and inspiring others by sharing what we learn.

In a broader context, 2020 marks another impressive milestone: the 250th anniversary of the founding of the Carmel Mission and Royal Presidio of Monterey. The settlement of the Monterey Bay region is intertwined with the lands of The Preserve and the people who helped shape it, and our hills and valleys are steeped with this historical and cultural legacy. Historian Mark Miller’s recently published book, The History of Rancho San Carlos, helps illuminate the lives of many of these historical figures. Who were these people, and what was their relationship with this land?

The indigenous Rumsen Ohlone tended these 20,000 acres for thousands of years by planting and caring for oaks, stewarding wildlife resources and setting low-intensity fires as a tool to maintain woodland health, ensure wild berry production, renew grasslands for deer and Tule elk, and clear brush to improve stream flows where sea-run steelhead trout return each year to spawn. One of their central villages, Echilat, was located very near today’s Hacienda, along the banks of Garzas Creek and the wetland complex that later became Moore’s Lake. The Preserve’s 46 known archeological sites speak to the richness of our meadows, forests and streams.

The founding of the Misión de San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo in 1770, later built of stone quarried not far from the gates of today’s Preserve, marked the end of this way of life for the Rumsen people and the beginning of the European settlement of central California. Even as the priests sent their livestock to graze on the rich grassland along what is now The Preserve’s Potrero Canyon, new diseases and rapid habitat degradation caused by invasive species from Spain proved disastrous for the Rumsen people. Echilat, a thriving community for over 3,000 years, was largely abandoned in less than a decade. Yet the Mission era itself spanned only a single lifetime, and less than 70 years later, both the native villages and the Mission community that absorbed their people were relegated to history.

The Mexican Government secularized the Mission in 1833, and by 1835 most of the native population had left Mission San Carlos at Carmel. They were officially given small land allotments by the priests. Several of these were on today’s Preserve lands, which became part of two Spanish Land Grants: “El Potrero de San Carlos” and “San Francisquito.” Wealthy Spanish Mexican provincial citizens soon took ownership of various portions of the land. Though they never lived here, the locally fabled Munras family used the lands to raise cattle for hide and tallow and to harvest timber and other resources. The Preserve and neighboring lands were favored hunting areas, particularly for grizzly bears, which were captured in traps or on horseback and brought back to the Presidio in Monterey to fight with bulls for sport.

The Anglo-American period from 1842-1923 consisted of a series of three family ownerships, also largely focused on commercial uses such as timber harvest, mining and raising livestock. In 1857, the Sargent Brothers assembled both land grants into a single 23,000-acre property and christened it ‘Rancho El Potrero San Carlos y San Francisquito.’ The rich natural resources and incredible resilience of its grasslands gave the ranch a reputation among stockmen for pastures able to restore malnourished livestock back to health, and cattle raised on the ranch were considered premium animals. During this period, the Hacienda began to take form, built on the site of older adobe structures.

The Jazz Age era brought a whole new flair to the Hacienda and its environs. George Gordon Moore was an industrialist, horse breeder and polo enthusiast. He brought new fame to Rancho San Carlos as the Hacienda became a fabled location for parties and liaisons. In 1930 he dredged and deepened the natural wetlands to form Moore’s Lake, and ranch roads opened more of the property to hunting and grazing. Moore’s investment enabled him to maintain the ranch as a recreational retreat for many years, but the dramatic financial losses of the Great Depression ultimately forced its sale.

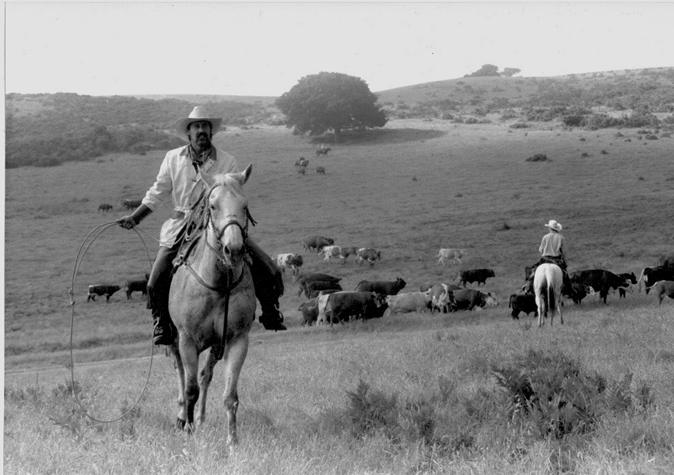

The final half-century of single-family ownership, from 1939 through 1990, began when the Oppenheimer clan, noted for innovations in the commercial fruit growing industry, purchased these 23,000 acres as a family getaway and private hunting estate. Under their ownership, the ranch sustained its most sizeable commercial beef operation, with up to 1,000 cattle managed by employees.

After three generations, divergent family ambitions led to a decision to sell the ranch as a single parcel to the Rancho San Carlos Partnership (led by Tom and Alayna Gray and Peter Stocker) in 1990. Their vision of sustaining the cultural and ecological integrity of the land as a model of community conservation carries forward all the best elements of its history – from native village, through family-run ranch and recreational retreat, to a vibrant and innovative example of community-based land stewardship. Through a rigorous, science-based process, homes were sited to avoid sensitive habitat and fire-prone areas, taking advantage of historic land uses and ranch roads to minimize new disturbance and ensure the permanent protection of an astonishing 90% of the property. To allow for the recovery of historically over-burdened grasslands, livestock were removed from the property, and protections put in place to ensure future grazing would be managed by the Conservancy for restorative purposes.

Today, over a hundred families help care for this land. Carefully managed cattle have returned to our abundant native grasslands, including the heritage breed that the Spanish brought with them hundreds of years ago. This conservation grazing program is allowing us to mimic natural disturbances such as low-intensity grassfires, restoring important ecological processes and supporting the health of our meadows and savannas. Mountain lions and black bears still roam these hills and valleys, and Rumsen descendants collect acorn and tule each fall. The Santa Lucia Conservancy is proud to be a member of The Preserve community, serving as a resource, partner and guide. We are excited to move forward together into a new decade and the latest chapter of this storied land.

BY CHRISTY FISCHER