A tick “questing” for a host. Photo Courtesy of Tick Proof.

It’s Tick Season in Central California

March 11, 2022

By Alix Soliman, Communications & Outreach Coordinator

Ticks are blood-feeding parasites that seek hosts through a behavior called questing, where they crawl up to the ends of grass stems or perch on the edges of leaves with their front legs extended. In our region, many ticks in the nymph stage (which are juveniles, about the size of a poppy seed) of their life cycle are most actively biting from March through August, while adult ticks are most commonly found from October through June.

When you’re getting ready to recreate or work outdoors, wear a long-sleeved shirt and long pants tucked into boots or socks. Wearing light colored clothing is best for spotting ticks that have hitched a ride. You can also use insect repellents, particularly around your waist, wrists, and ankles where clothing shifts and exposes skin. Before returning home, make sure to thoroughly check yourself for ticks.

To keep your pets safe, talk to your veterinarian about topical treatments that prevent ticks, as well as the Lyme Disease vaccine that is available only for dogs. Make sure to groom your pet after taking them for a walk, as ticks may hang onto their fur for several hours before biting.

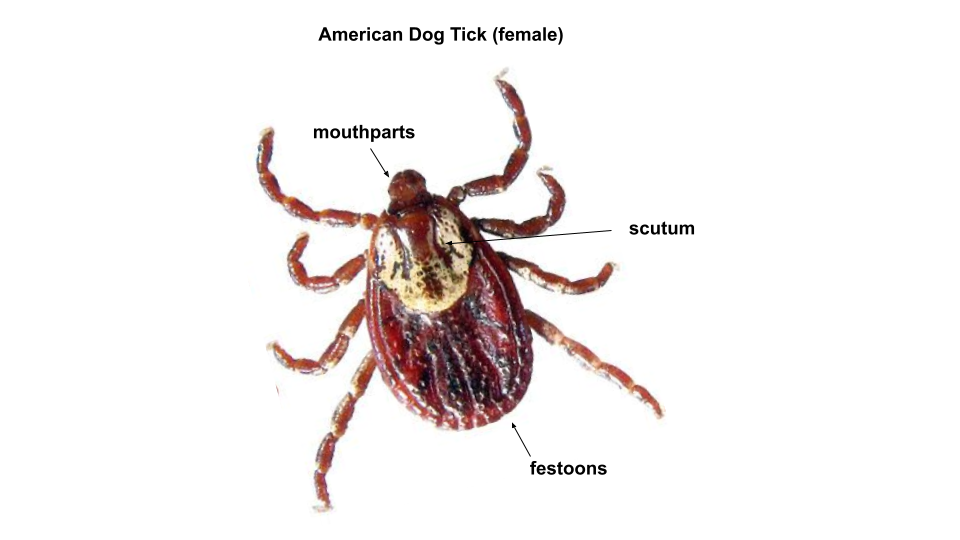

How to Identify Common Ticks in California

Ticks are arachnids, and the species you may come into contact with in California have three main parts that help with identification: 1) the scutum, which is the shield on their top side that does not change size even when the tick engorges, 2) the mouthparts that embed in your skin, and 3) festoons, which are the grooves found on the thin line at the back of most tick species, but are not found on the Western blacklegged species. Because ticks are so small, it can help to use a magnifying glass or take a photo to identify it.

Western blacklegged tick or deer tick (Ixodes Pacificus)

This is the tick responsible for transmitting Lyme Disease in California, and it is also a vector for Anaplasmosis. It can be identified by its dark scutum, reddish body color, long narrow mouth parts, and lack of festoons. It looks very similar to the Eastern blacklegged tick, also known as the deer tick, but has a slightly more elongated body.

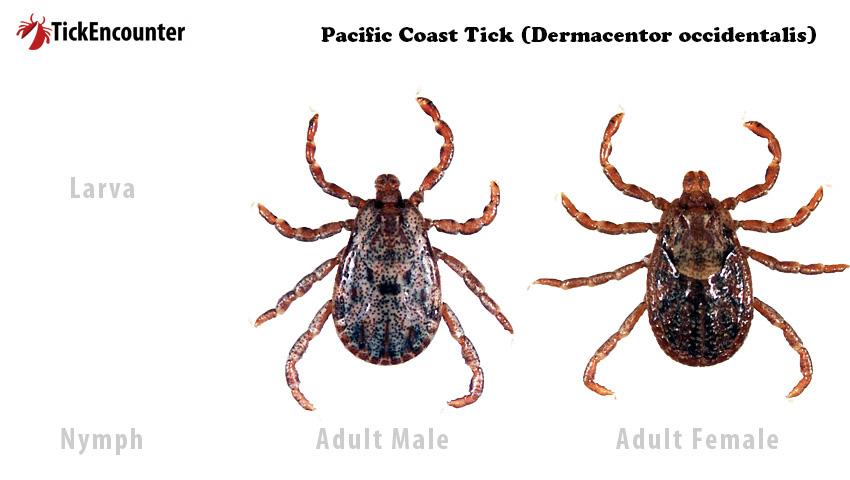

Pacific Coast tick (Dermacentor occidentalis)

This species is a vector for Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, Colorado Tick Fever, Pacific Coast Tick Fever, and the rare disease Tularemia. Both the scutum and the main body of this species is a mottled brown color, with smaller mouth parts, and festoons that match the color of the rest of the body.

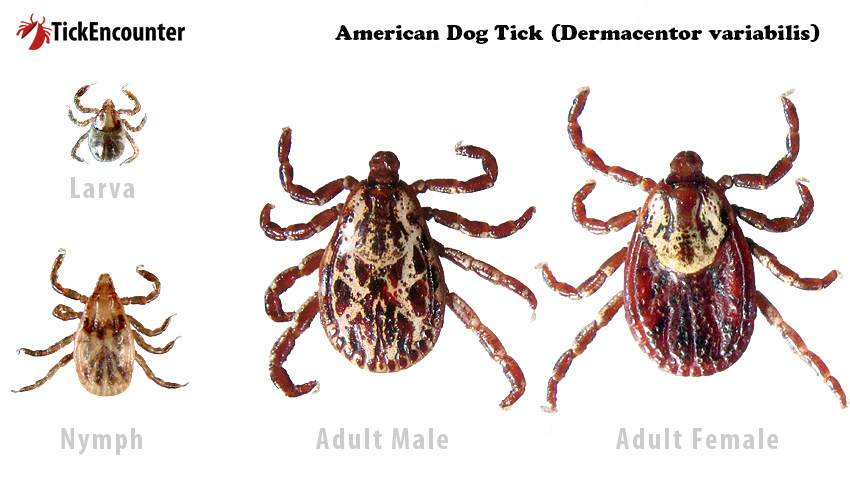

American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis)

This species is a vector for Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and Tularemia. It has a cream and red sctutum, red or mottled cream and red body, short mouth parts, and festoons that match the rest of the body.

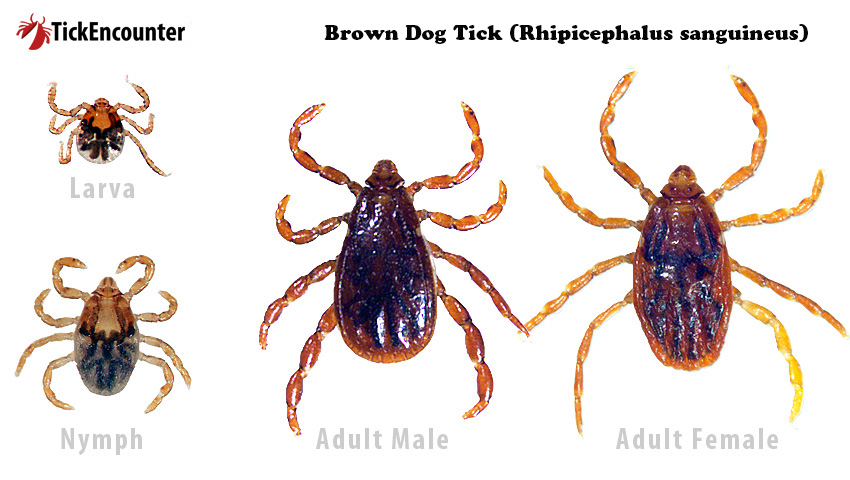

Brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus)

This species can be a vector for Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever. In the adult stage, the maroon or maroon and orange scutum is almost indistinguishable from the body. It has the smallest mouth parts of the species we’ve listed here, and the festoons and legs are a lighter amber color than the rest of the body.

How to Remove a Tick

As soon as you find a tick on yourself, a loved one, or pet, remove it with tweezers or a tick key. To avoid encouraging the tick to dig in deeper, do not fiddle with the tick or skin immediately around the bite until you’re ready to pull it out.

If you’re using tweezers, grab the tick firmly as close to the skin as possible and pull steadily straight out, without twisting. It’s important to do it correctly, because if the mouthparts of the tick are left in the bite they could lead to infection. Once removed, clean the area with soap and water, apply antiseptic, and check to see if you got the whole tick or if the mouthparts remain in the bite. If the mouthparts are still in the skin, try removing them with sterilized fine-tipped tweezers or see a healthcare professional.

How to Send a Tick in for Testing

After you’ve removed a tick, you can place it in a plastic bag and send it to Tick Report or Tick Check for lab testing. While many ticks don’t carry pathogens, having them tested is the best way to determine your risk of infection.

All photos courtesy of TickEncounter.